“Can’t, or won’t?” I asked the nice lady at the counter.

She smiled but remained silent, hanging firmly onto what I presumed to be a canned response. Hard to imagine I was the first (or last) person she spoke to about this.

I tried to negotiate a win-win deal without having to call Howie Mandel. As a business owner myself, I felt an obligation to make something work before deciding to take my money elsewhere. I wanted to support this local yoga studio, but I also don’t like paying for things I don’t use.

She gave me three options:

A single drop-in class for $15 = $15 per class

A package of 5 classes for $50 = $10 per class

An unlimited monthly membership for $100

I was visiting a town for three days with my partner and we both like to do yoga as part of our daily health regimen. We’re digital nomads, which means a monthly membership to a local venue usually doesn’t make sense for us.1

So really, I had two options: pay for three drop-in classes for $45 or buy a 5-class pass for $50 and waste two of the classes (which effectively equates to paying about $17 per class). We needed a total of six classes but $90 just seemed like way too much to pay.

One doesn’t need a degree in mathematics to see the solution here: buy one 5-class pass and one extra drop-in class. Instead of paying $90, we could pay $65 for our daily dose of zen. Anything more would be a waste of money.

But for some reason, the lady at the counter didn’t see the genius of my arithmetic.

“Sorry, we can’t do that.”

Apparently sharing classes wasn’t allowed. We could pay $90 for six classes, $100 for 10, or $200 for 60. The unit economics just didn’t add up for me.

We went home, rolled out our mats, and turned on a Youtube video.

Namaste.

Idle Supply, Meet Uncaptured Demand

Rigid pricing structures like this force a zero-sum game where one wins, or both lose.

The class had plenty of space for us, but the price wasn’t right. Perhaps we could’ve met in the middle somewhere. After all, the costs to the business don’t necessarily increase with each additional body in the room. I can’t help but wonder if the owner would’ve rather booked us at a lower rate than not book us at all. I know I would’ve.

How many others get turned away, each one a statistic of lost revenue that never shows up on a sales report? You’d think a yoga studio would be more flexible.

When Amber Carpenter started studying revenue management for vacation rentals, she stumbled upon a surprising metric: 50% of booking queries returned “no result” for website visitors.

Meaning HALF of all the people visiting these sites, who were ready and willing to spend their money, literally couldn’t because the purchase parameters were too rigid. The pricing model could not accommodate the wide array of user needs.

It’s not that there were no rentals left to sell, it’s that the knobs and levers that enabled those sales were getting rusty. Property management companies thought they were meeting all of their customer’s needs. But they were wrong. Each “no result” translated to “Sorry, we can’t do that.”

Her discovery became known as uncaptured demand, and went on to change how recommendation engines are designed for vacation rental booking sites. Today, when you can’t find exactly what you’re looking for, you now see alternative options designed to help you buy something instead of nothing.

It’s not “Sorry, we can’t do that,” it’s “How about this instead?”

Pricing for the Long-Tail

Even if business owners could quantify the amount of money that’s getting left on the table, would they care enough to do something about it?

There’s a maximum price I’m willing to pay for a yoga class, and there’s a minimum price the owner of a yoga studio is willing to accept. In the space between these two numbers is something I call “minimum viable value” (MVV)—the point at which both parties feel they’ve received fair enough value to do the transaction.

No undue loss or waste. No value deficit on either side of the aisle.

Just pure economic equilibrium.

As long as the owner isn’t losing money and I’m not overpaying, the dance floor is open and there’s room to tango.

But the MVV isn’t typically transparent or easily available. Even if it were, there’s not an easy way to scale the negotiations. So the owner is stuck playing a guessing game, settling on a probabilistic pricing model that’s built for the masses instead of an adaptive model that caters to more nuanced user needs.

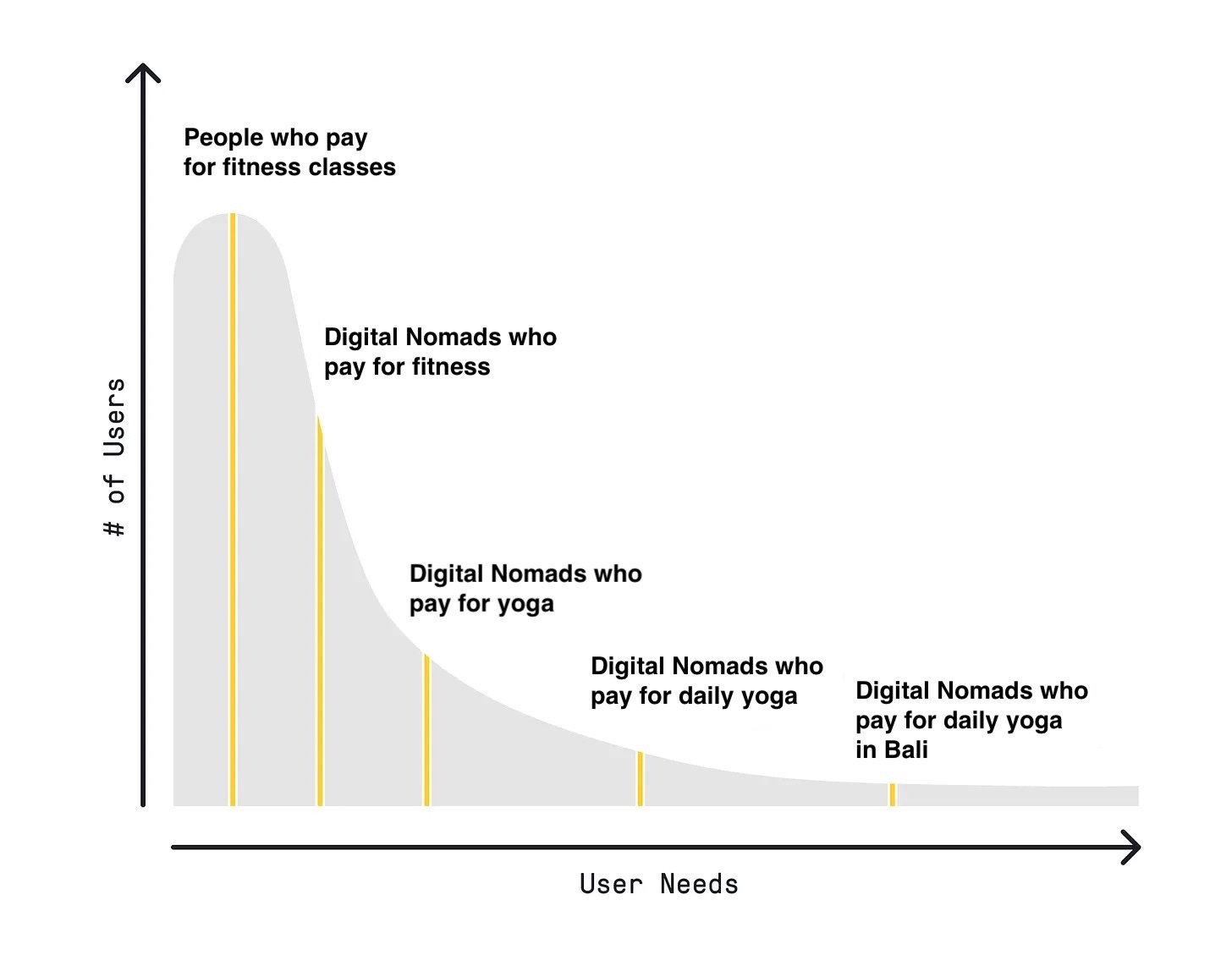

This is what Kasey Klimes calls the long-tail problem2…

Instead of tailored solutions that strive for the MVV, the uncaptured demand is swallowed up by cookie-cutter capitalism. The standard pricing models are built for the majority of users serving the most common use-case.

And for good reason.

There’s not a lot of incentive for all the yoga studios in Bali (or anywhere for that matter) to offer a pricing structure that meets the needs of a such a small niche.

So the spandex-wearing yogini who wants to contort her body in new cities every month is stuck with a price tag that’s designed for scale instead of scaled by design. She lives in the margins of value deficit.

She’s not too salty about it, but she knows there are better ways of doing business.

These deficits aren’t just limited to yoga studios in remote island villages. They’re found in many products and services we use every day. This is a problem. But not an unsolvable one. In fact, some companies have already started to retrofit their prices.

And next week, I’m going to tell you why.

Unless it’s part of our all-inclusive life.

Graph adapted from Kasey’s original post for illustrative purposes.